Are Millennials really killing the Tory party?

By Bobby Duffy and Paul Stoneman

Millennials are the deadliest generation in history, killing everything from marriage to the napkin industry, the Olympics to marmalade.

And now they’re accused of destroying another long-standing tradition – the political lifecycle.

In much more important and interesting analysis than those other examples of Millennials’ destructiveness, John Burn-Murdoch outlined in the Financial Times how Millennials are breaking the pattern of voters becoming more “conservative” as they get older. The generation born from 1980 to 1995 are staying stubbornly way below average levels of support for conservative parties in the UK and US, despite the oldest of the cohort now being in their early 40s – ruining the multi-attributed quip that “if you are not a liberal at 25, you have no heart. If you are not a conservative at 35 you have no brain”

The data show a quite remarkable shift, which reflects a very real challenge for the Conservatives in the UK and Republicans in the US.

There are, however, two important qualifications that make the generationally driven death of either party less certain than it may seem.

First, the FT analysis compares Millennial voting patterns to the average level of support for the Conservatives and Republicans, showing that they are not moving closer to that average as they age. This approach makes sense, because the political context is constantly changing, with party ratings rising and falling, and the average is a key reference point in understanding how different generations are moving.

But it’s inevitably a partial measure, because that average is affected by all generations: if you have an unusually high level of support in an older generation, it will be much harder for younger generations to catch up with the average.

And in the UK we do have the most fervently Conservative cohorts of older people that we’ve ever seen. Support for the Conservative party has had a strong generational gradient since at least the 1980s when these surveys began – but the gap in recent years is of an entirely different order. As our new analysis shows, there was a 40-percentage-point range from oldest to youngest in 2020, compared with half that in the early 2000s, and only 10 percentage points in the early 1990s. This is driven by unusually high levels of support for the Conservatives among older generations, as well as unusually low levels of support for the party among younger generations (including Gen Z, not just Millennials).

In many ways, Labour support has seen an even more extraordinary shift. We’ve very quickly got used to the idea that Labour’s vote is much younger – but this is a completely new pattern. In fact, Labour support has traditionally been incredibly evenly spread across the generations, back to the early 1980s. But that changed suddenly, in the run-up to, and aftermath of, the Brexit vote – and, setting aside the huge dip in Labour support around Corbyn’s leadership, is now at an unprecedented 30-point gap between youngest and oldest.

There is more to the generational patterns in party support than Millennial exceptionalism.

And there is another reason to be a little cautious in seeing this as a clean break from previous patterns.

The FT analysis does a great job in outlining the importance of looking at political support as driven by a mix of “age, period and cohort effects”. That is, how people vote can be related to what stage they are in their lifecycle (age), what’s happening right now in politics (period) and what generation they were born into, and so what was happening in their formative years or how their life chances have been shaped as a result (cohort). All change is explained by a mix of these three effects and understanding the balance between them is key to understanding the future.

We’ve used this incredibly helpful framework to look at change across a wide range of issues – and, out of all these varied topics, politics is by far the most complex and unpredictable mix of effects. Patterns that look utterly set change quickly. Rules that seem completely broken reassert themselves.

For example, concern about voter turnout among younger generations peaked in the 2010s, just as the last Millennials were making it to voting age. The suggestion was Millennials did not see voting as a duty, rather, they regarded it as the duty of politicians to woo them. As an Economist piece put it, “[t]hey see parties not as movements deserving of loyalty, but as brands they can choose between or ignore.”

And the data backed that up. In 2010, only a half of Millennials said it was their duty to vote, compared with nine in 10 in the oldest generation, and this seemed like a settled pattern.

But then the UK went through an incredibly turbulent political period from the mid-2010s, with two highly charged referendums and three bitter general elections in five years, and it all shifted again. Millennials came much more into line with other generations in their views on the importance of voting, as they aged and events shaped them.

We can also track the extent to which there is a generational divide on big questions like government expenditure – and on key areas such as the balance between welfare and taxation, younger generations do not come across as particularly left-leaning. The chart below plots generational patterns in support for increasing welfare spending even if it leads to increases in taxation. It shows that younger generations tend to be less supportive of increases in welfare spending, a pattern that continued with Millennials. This makes sense given older generations who are coming out of the labour market will be less affected by increases in tax – and the generational pattern doesn’t show the significant break from the past that you might expect if there had been a fundamental shift towards conservative preferences.

It also shows no sign of increasing generational division: if anything, the different cohorts are coming closer together. Instead, it more clearly demonstrates the power of period effects, where all generations have followed a similar long swing, of markedly decreasing support for welfare up to 2010, then a gentler drift to increasing support from the mid-2010s.

Politics is replete with gnomic sayings about change. “Events, dear boy, events” from Harold Macmillan and “A week is a long time in politics” (supposedly) from Harold Wilson are just as overused as the political lifecycle quote for a reason: period effects matter. We are definitely witnessing a significant age-driven shift in party support, but it may not be a break in the political lifecycle rule so much as a rejection of current versions of Conservatism and Republicanism among younger generations that could quickly shift again.

There is no mystery at all why younger generations would be turning their backs on the current offer. Policy choices have repeatedly favoured older people, such as protecting pensions and propping up a broken housing market, whilst ignoring issues like childcare provision. Added to that, there are headwinds that would have hit any party in power as generation-on-generation economic progress ground to a halt as economic growth stalled, with Millennials bearing the initial brunt of this stagnation.

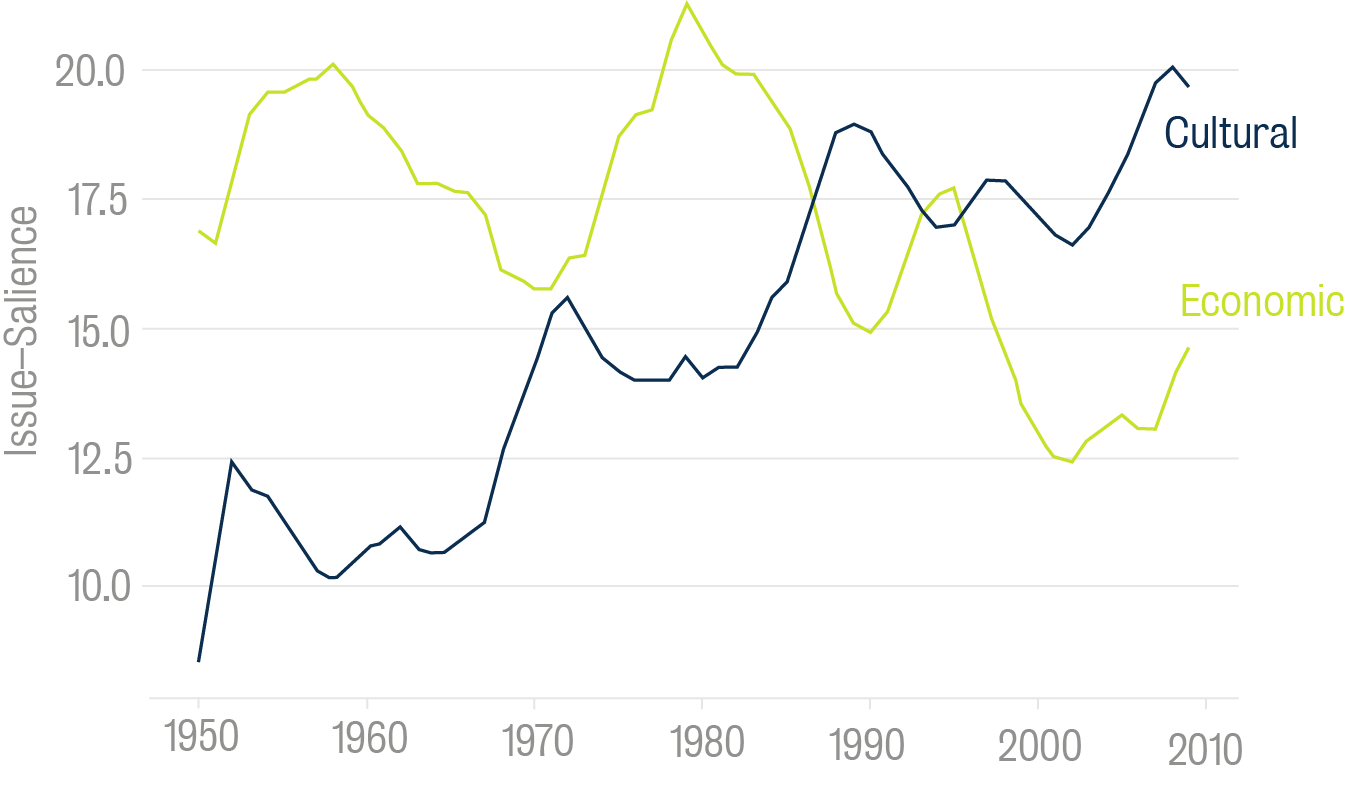

And there is a second strand – culture change has been put at the heart of politics much more than in the past. This is a long-term trend, as shown in a fascinating study of party manifestos across 21 Western democracies, where the number of promises focused on cultural and values issues has doubled since the 1950s as the number of economic promises declined. In the UK, Brexit amplified this cultural turn in politics centred first on immigration and subsequently evolving more widely into “woke versus anti-woke” issues.

Changes over time in the relative prominence of economic and cultural issues in the party manifestos of Western democracies

Source: Comparative Party Manifesto Dataset, in The Electoral Politics of Growth Regimes, Cambridge University Press, 18 June 2019, Peter A. Hall. Note: proportion of references to each type of issue in party manifestos weighted by party vote share in the most recent election for each country

Whenever you put a binary battle over cultural visions at the centre of politics, you are building in an age division. There is an immutable truth that younger groups will, on average, be more comfortable with changing social norms than older generations, and that’s certainly the case on the “culture war” issues we’ve seen increasing focus on. As the charts below show, there are steep age gradients on attitudes to political correctness and free speech, trans rights and the British empire.

A vital point to bear in mind, however, is that there is always a strong difference between old and young on emergent social issues. The chart below is from surveys in the mid-1980s, when Baby Boomers were the younger adult generation, and shows that they were half as likely as their parents and grandparents to agree that men should go out to work and women should stay at home. The issues have changed but the gap between generations hasn’t markedly shifted. The real difference between then and now is how central these issues have become to party politics.

But there are forces that attenuate the impact of these economic and cultural assaults on the interests of younger generations. In particular, they have emerged at the latest point in a long-term cultural tide towards individualism, where the rise in values of self-expression has gone hand in hand with a greater emphasis on personal responsibility for life outcomes. This is particularly marked in the UK (and Ireland), which often come out as the most individualistic countries in Europe, and much closer to the US.

The Conservative and Republican parties have helped push us along this long-term path.

Margaret Thatcher’s 1975 Conservative party conference speech is an excellent example of this political worldview: “We believe [people] should be individuals. We are all unequal. No one, thank heavens, is like anyone else, however much the Socialists may pretend otherwise.” Ronald Reagan was a fellow staunch supporter of “rugged individualism”. In his famous “A Time for Choosing” speech in 1964, he described his resentment at the tendency in some quarters to refer to the people as “the masses” and asserted that individual freedom was still the best approach to solving the complex problems of the 20th century.

Younger generations today grew up in the context set by this long shift and have a particularly strong sense of personal responsibility for how life turns out. They have tended to blame themselves.

We saw that in a survey we conducted in 2022, which examined how the different generations viewed each other. One of the questions tested a statement based on an interview with TV personality Kirstie Allsopp, where she suggested that young people couldn’t afford to own their own homes because they spent too much on Netflix, gym subscriptions, fancy coffees, delivery food and foreign holidays. Distressingly, half of the public agreed – and, even more distressingly, Millennials and Gen Z were just as likely to agree as older generations.

This sense of personal responsibility and belief in meritocracy may be strong, but it has limits. As very useful analysis from Ben Ansell shows, younger people are now much less likely than older people to believe that economic success is down to individual effort, and much more likely to think it is down to “outside forces”. Even if the growing gap between expectation and reality doesn’t lead to revolution, it certainly inspires growing resentment and a dwindling faith in a better future. This is the real political challenge, and opportunity, for Labour – they have a natural advantage with these younger generations, but it will quickly dwindle if they don’t present a more hopeful generational vision.

The death of the Conservative party has been incorrectly predicted repeatedly, and there are good reasons to be sceptical we’re seeing their automatic, generationally driven end now. These are policy and positioning choices, not yet a political destiny driven by demographics. The generational pattern facing the Conservatives is certainly dire, and they need a significant reinvention, but Labour also can’t just rely on a rising generational tide – they need to listen carefully to Millennials and Gen Z.

Bobby Duffy is Professor of Public Policy and Director of the Policy Institute, King's College London.

Dr Paul Stoneman is a Research Associate at the Policy Institute, King's College London.